Veterans Memories

Tony Ramblings Story

I was a Gunner W Op on an armoured car in Lt Williams troop B Squadron he married Chottie , her daughter wrights the blog on Chottie Darling. She came to see me to get info for the blog. you wanted a story.

The first 40 days or so was very hard getting from the beaches to Caen. We didn't even take our boots off and were unable to wash very much if you did you heated up a biscuit tin of water with a biscuit tin below it filled with earth and some petrol. Slept in a slit trench 2 blankets and a ground sheet to avoid getting shrapnel form mortars. A few miles from Caen we had to park our vehicles and file up to the front line were we went into trenches. At a place named Briquessard , these trenches were at the bottom of a forward sloping wood just 2 small fields away from the Germans in their trenches. Mortar bombs were exchanged and gun fire often in the night. We were in these trenches 10 days the only sleep you could get was standing up in the trench, Food was brought down to us at night. We also had to man outposts which were in no mans land about 40 yards from the trench line, with a field telephone to warn of a attack.

Could go on. Please excuse typing for a 90 year old.

Tony

I was a Gunner W Op on an armoured car in Lt Williams troop B Squadron he married Chottie , her daughter wrights the blog on Chottie Darling. She came to see me to get info for the blog. you wanted a story.

The first 40 days or so was very hard getting from the beaches to Caen. We didn't even take our boots off and were unable to wash very much if you did you heated up a biscuit tin of water with a biscuit tin below it filled with earth and some petrol. Slept in a slit trench 2 blankets and a ground sheet to avoid getting shrapnel form mortars. A few miles from Caen we had to park our vehicles and file up to the front line were we went into trenches. At a place named Briquessard , these trenches were at the bottom of a forward sloping wood just 2 small fields away from the Germans in their trenches. Mortar bombs were exchanged and gun fire often in the night. We were in these trenches 10 days the only sleep you could get was standing up in the trench, Food was brought down to us at night. We also had to man outposts which were in no mans land about 40 yards from the trench line, with a field telephone to warn of a attack.

Could go on. Please excuse typing for a 90 year old.

Tony

Derek Edmonds Story

OK, after Scarborough I was a driver/wireless operator, in the Recce you were trained to be drivers/w/ops or driver/ mechanics or driver/ assault troopers. After that including Assault Courses one of which was firstly to ford a river up to your armpits then climb a hill, at the top of which there was another hill, then another, then another, by the time you reached the top you were dry and a 3 tonner back to base. After some time in a convalescent depot, then to Catterick Camp, then to a training Regiment near Heysham where you crawled along ditches whilst they fired machine guns over head on the Lancashire moors on weekly exercises on the moors, finally to the 61st Recce Regiment near Duxford and then to some woods near Romsey getting ready for D Day. Exercises getting on and off Landing Ship Tanks and then 7 days afloat between the Isle of Wight and the mainland, all of a sudden we rounded the end of the IOW and headed for France. The LST's had bows which opened, a huge raft was fastened to the bows, on to it we drove and we were dropped into 4 feet of water and we drove off the beach and laagered about 2 miles inland to await the rest of the Regiment. Next morning the troop of 4 carriers did our bit, we entered a wood from open ground and the lead carrier was fired on from a Jerry machine gun nest at the side of the road, the Corporal in charge was wounded, he threw a mills bomb at the Jerries, they threw it back and he threw it back, where it exploded, we retired to the beginning of the wood the Corporal lolling back, wounded, we saw some more Jerries on the other side of the hedge about to fire and one of our chaps got him first, we then withdrew further back. My part was to report back, and yell out Er Geben si sich which meant Surrender yourselves. Remember the Reconnaissance role was to draw fire, retire and report back which is what we did. The Corporal got the MM for that episode. I was wounded slightly a few days later, but that's another story. From the Extremely Elucid Ex. Wireless Operator.

" I ask Derek if the training at Scarborough was Tough"

Yes, it was, after the wireless training which included Morse at 10 words a minute and learning to drive we spent a lot of time on the Yorkshire Moors where the assault courses were. I was still only 18 so was pretty fit. We didn't get a lot of free time to look at Scarborough. It was the 1st time I was away from home and it was 5 months before I got any leave. At Catterick we did go out on some exercises but I wasn't there long. The Troop Sergeant caught me mimicking comedians on the wireless, right he said you to the sergeants mess on Saturday night. After my act(which wasn't very good) the Regimental Sergeant Major bought me pint of beer, then the Staff Sergeant bought me a pint and finally a Sergeant bought me one, when I got on my feet my legs had turned to rubber, I danced across the parade ground back to the hut and was sick as a dog.

OK, after Scarborough I was a driver/wireless operator, in the Recce you were trained to be drivers/w/ops or driver/ mechanics or driver/ assault troopers. After that including Assault Courses one of which was firstly to ford a river up to your armpits then climb a hill, at the top of which there was another hill, then another, then another, by the time you reached the top you were dry and a 3 tonner back to base. After some time in a convalescent depot, then to Catterick Camp, then to a training Regiment near Heysham where you crawled along ditches whilst they fired machine guns over head on the Lancashire moors on weekly exercises on the moors, finally to the 61st Recce Regiment near Duxford and then to some woods near Romsey getting ready for D Day. Exercises getting on and off Landing Ship Tanks and then 7 days afloat between the Isle of Wight and the mainland, all of a sudden we rounded the end of the IOW and headed for France. The LST's had bows which opened, a huge raft was fastened to the bows, on to it we drove and we were dropped into 4 feet of water and we drove off the beach and laagered about 2 miles inland to await the rest of the Regiment. Next morning the troop of 4 carriers did our bit, we entered a wood from open ground and the lead carrier was fired on from a Jerry machine gun nest at the side of the road, the Corporal in charge was wounded, he threw a mills bomb at the Jerries, they threw it back and he threw it back, where it exploded, we retired to the beginning of the wood the Corporal lolling back, wounded, we saw some more Jerries on the other side of the hedge about to fire and one of our chaps got him first, we then withdrew further back. My part was to report back, and yell out Er Geben si sich which meant Surrender yourselves. Remember the Reconnaissance role was to draw fire, retire and report back which is what we did. The Corporal got the MM for that episode. I was wounded slightly a few days later, but that's another story. From the Extremely Elucid Ex. Wireless Operator.

" I ask Derek if the training at Scarborough was Tough"

Yes, it was, after the wireless training which included Morse at 10 words a minute and learning to drive we spent a lot of time on the Yorkshire Moors where the assault courses were. I was still only 18 so was pretty fit. We didn't get a lot of free time to look at Scarborough. It was the 1st time I was away from home and it was 5 months before I got any leave. At Catterick we did go out on some exercises but I wasn't there long. The Troop Sergeant caught me mimicking comedians on the wireless, right he said you to the sergeants mess on Saturday night. After my act(which wasn't very good) the Regimental Sergeant Major bought me pint of beer, then the Staff Sergeant bought me a pint and finally a Sergeant bought me one, when I got on my feet my legs had turned to rubber, I danced across the parade ground back to the hut and was sick as a dog.

Harry Rankin

My father, Norman Harry Rankin, told me a few stories about he's days in the Recce core. I thought that others might want to hear them. Maybe they or their Fathers were involved: They were in France and had run out of fuel for the Bren gun carrier he was driving. They went into a barn in a farm yard and dug up the floor inside. Under the floor they found some Calvados brandy, they put it in the fuel tank and my father adjusted the carburettors and got the Bren gun carrier running.

They were trapped in a large greenhouse and the Germans were firing at them with machine guns.

In the green house there were grapes. They ate the grapes and at night the farmer’s wife brought them a large bowl of yoghurt. He said she was a brave woman. Because of this he would not eat grapes or yoghurt after the war.

One of the men in his group was a Mr McAlpine. I think he was one of family that had a construction firm.

They drove into a town or village square and there was a German tiger tank in the square. My father put the Bren gun carrier into reverse and drove out of the square. He spun it around and drove through a hedge. The tiger tank drove through a shop and emerged out in the back garden but was too late to fire at them as they went over the ridge of the field and down the other side.

I have a German snipers rifle bullet that has a dent in the end. My farther said that he was sitting in the driver’s seat and moved his head to look at something when the bullet hit a pipe or something just behind his head.

I hope others will find these interesting. My mother would not let him talk about what happened during the war, so these are the only stories I have.

Regards

Ken

My father, Norman Harry Rankin, told me a few stories about he's days in the Recce core. I thought that others might want to hear them. Maybe they or their Fathers were involved: They were in France and had run out of fuel for the Bren gun carrier he was driving. They went into a barn in a farm yard and dug up the floor inside. Under the floor they found some Calvados brandy, they put it in the fuel tank and my father adjusted the carburettors and got the Bren gun carrier running.

They were trapped in a large greenhouse and the Germans were firing at them with machine guns.

In the green house there were grapes. They ate the grapes and at night the farmer’s wife brought them a large bowl of yoghurt. He said she was a brave woman. Because of this he would not eat grapes or yoghurt after the war.

One of the men in his group was a Mr McAlpine. I think he was one of family that had a construction firm.

They drove into a town or village square and there was a German tiger tank in the square. My father put the Bren gun carrier into reverse and drove out of the square. He spun it around and drove through a hedge. The tiger tank drove through a shop and emerged out in the back garden but was too late to fire at them as they went over the ridge of the field and down the other side.

I have a German snipers rifle bullet that has a dent in the end. My farther said that he was sitting in the driver’s seat and moved his head to look at something when the bullet hit a pipe or something just behind his head.

I hope others will find these interesting. My mother would not let him talk about what happened during the war, so these are the only stories I have.

Regards

Ken

J Heitman

Hello Dave. a brief resume on how my Dad got the Purple Heart.

When Dad was serving with 61st RECCE he was an Liaison Officer between the British Forces and the U.S. 101st Airborne Div Known as the Screaming Eagles ,Dad was wounded by a shell exploding above his armoured car and he was temporarily blinded. Dad was taken to a U.S. Hospital to recover, After a short time his sight returned, as you know the Purple Heart is awarded for wounds sustained in time of War.

General Patton came to the hospital and walked down the ward saluting and handing out the medals to all the wounded soldiers. Strictly speaking Dad was not allowed to wear the medal as it is only awarded to U.S. citizens but I have been in touch with the Purple Heart society and they stated that as it was Gen Patton that gave Dad the medal and he was the area Commander at that time the powers that be would not say otherwise. I still have the medal, and is one of my treasured possessions from my Dads time in the Army.

Hello Dave. a brief resume on how my Dad got the Purple Heart.

When Dad was serving with 61st RECCE he was an Liaison Officer between the British Forces and the U.S. 101st Airborne Div Known as the Screaming Eagles ,Dad was wounded by a shell exploding above his armoured car and he was temporarily blinded. Dad was taken to a U.S. Hospital to recover, After a short time his sight returned, as you know the Purple Heart is awarded for wounds sustained in time of War.

General Patton came to the hospital and walked down the ward saluting and handing out the medals to all the wounded soldiers. Strictly speaking Dad was not allowed to wear the medal as it is only awarded to U.S. citizens but I have been in touch with the Purple Heart society and they stated that as it was Gen Patton that gave Dad the medal and he was the area Commander at that time the powers that be would not say otherwise. I still have the medal, and is one of my treasured possessions from my Dads time in the Army.

Don AIKEN, B Squadron, 61st Reconnaissance Regiment, Reconnaissance Corps

Normandy June 1944

“We arrived off the shore of Normandy in the late morning. 'Gold' Beach near the village of Arromanches, which was our first destination, had already been captured by the assault troops of the Hampshire Regiment, and it was now possible for vehicles to be disembarked on to the beach and directed to designated areas for the purpose of de-waterproofing the vehicles and preparing to advance into the bridgehead.

The LST dropped anchor and the remaining Rhino was untied from the side of the ship and made its way round the bows, ready to be attached to the gangway which projected forwards when the bow doors opened. It was then discovered that the coupling gear had been smashed and this sparked off a frenzied burst of activity to try to tie the units together with ropes. However, ropes are flexible by necessity, and the choppy seas made it almost impossible to hold both units in line; but with the aid of a couple of small motor-boats, pushing away like tug boats, they became near enough to go for it and our Troop made the transfer across.

Soon we were running in to the beach and the Rhino bottomed out. The light armoured car (Recce Car) in which I was a crew member was the first to drive off, and in my elevated position in the turret I felt like a submarine commander, especially when we suddenly dropped into a bomb hole which was concealed beneath the water and only the turret was left exposed.”

“The Beach Party had been well trained for this situation and had the de-waterproofing area completely organised and running smoothly. Although I almost threw a spanner in the works!

My armoured car had been fitted with a device, which I had contrived, to allow me to operate the smoke canister gun without having to lean outside the turret. Basically, it was a bike brake mechanism, which was attached at one end to the gun and, at the other end, the brake grip was attached to my seat support. Whilst the driver was removing the waterproofing from the engine, the Officer went to a quick 'O' Group (Officers briefing) and the radio-operators tuned in their radio transmitters to the H.Q. transmitter. This was quite a delicate operation and it was at its finest point when my elbow touched against the trigger. Bang! went the smoke discharger - and as I quickly bobbed my head out I could see the smoke bomb heading straight into the middle of a wired off field, with dozens of painted notices showing the sign of a skull and cross-bones and the words "Achtung Minen". It didn't take a genius to recognise that my bomb was landing in a German mine-field, and the mines were too close for comfort.

I ducked down inside my turret and held my breath........ Nothing - oh good! Then Bang! Bang! Bang! ..... I realised it was someone banging on the turret. When I popped my head back out I was confronted with the angry face of the Beach Officer - a Major - whose features reminded me strongly of the Medical Officer with whom I had been acquainted in Scarborough; complete with black curly moustache, but perhaps even stronger on the language!”

“Soon the various sections of our Regiment were ready to move off to try to reach their pre-arranged target locations. Ours was a wooded hill about 15 miles inland, and our role was to 'seize and hold' it, until the main body of troops could relieve us. It was soon quite obvious that, because of our delayed landing, there was no possibility of us reaching our target that day.

As we drove off the beach, through a pathway made through the minefield and on to a narrow road that ran in a southerly direction, a huge anti-aircraft barrage opened up from the multitude of ships which lay offshore. As the barrage drew nearer I spotted a German plane flying very fast and very low as it fled southwards directly over our heads. I quickly joined the fading barrage and emptied my Bren gun magazine in the direction of the speeding ‘hornet’ as it disappeared out of sight. Despite my effort being in vain I felt great satisfaction in at last being able to throw things back at the Germans.

I remember nothing about our advance during the remainder of the day, only that we eventually had to give way to the coming of the night.”

“My only memories of that first night were that we had to remain standing in the pitch blackness, not daring to make a sound as we had no idea of how close we were to the Germans. We were fortified by a tiny drop of rum, which barely covered the bottom of our tin mugs, and a 'keep awake pill'. Nothing happened all night but we were all relieved when dawn broke and we were able to start off again.”

The Division had landed on Gold Beach, Normandy, on June 6th and fought through Europe up to Arnhem, Holland. Because of the reduction in personnel it was decided that the Division would be disbanded and the remaining personnel be transferred to other units. With this in mind we, 61st Reconnaissance Regiment, were sent back to a small town called Iseghem, which is situated in Belgium, close to the French border. We were billeted in various houses, cafe s and so on, and our H.Q. and cook-house was situated in the railway goods yard. All our vehicles and equipment were taken to a dump somewhere on the road to Antwerp. We had a few days of wonderful bliss. Nothing to do but have a few drinks in the cafe s and idle our time away.

We hadn't reckoned on the Germans. They had realised that the defensive strength of the US Army in the Belgian Ardennes forest was not good, with only 4 Divisions holding a front of 80 miles long. Hitler himself had ordered 3 Armies, totalling twenty-one Divisions (although well below strength), to be assembled in Germany ready for a huge counter-attack. This began on December 16th, meeting with great initial success and the American defence lines were cut to ribbons.

The situation was becoming very serious, as the whole 'sharp-end' of the Allied forces were in danger of being isolated. The British forces directed a push down from the north onto the advancing Germans. We were given 24 hours to reclaim our vehicles and equipment and move out to the Ardennes. This we did.

We arrived at Namur a few days before Christmas, and were immediately given the task of contacting a forward unit of US Engineers who had been instructed to blow a bridge over a small river ( I believe the Ourthe) whenever they sighted the German advance. The orders had now been changed to 'blow up the bridge regardless', but radio contact with the Engineers had been lost.

We set off on our mission and we were shocked to see convoys of US troops retreating in total panic. They threw us some fags and shouted that we were going the wrong way.

We approached our destination, and turned a corner to see that the road ran down into a steep valley, with a similar road running round and down the cliffs on the other side. At that moment we heard a loud explosion and knew that the bridge had been blown. We continued for a short way down the road before spotting the US Engineers running up behind the hedgerow and waited for them to arrive. It was then that I observed a German tank on the road across the valley and, almost immediately, a puff of smoke from his 88 mm. gun. There was a whoosh as the shell screamed over my head and took a lump out of the road and part of the tyre from the armoured car which stood a few yards behind me. Within a few seconds our armoured cars had disappeared up the road and round the corner, in reverse.

“After the huge gamble by the Germans to break through the Ardennes, which came to a disastrous failure, the 61st Reconnaissance Regiment was broken up during January 1945.

I was then posted to C Squadron of the 52nd (Lowland) Scots Recce Regt.. They had trained in Scotland for most of the war and bore a 'MOUNTAIN' flash on their tunics.

Strangely they had only seen warfare in mountainless Holland before I joined them on my birthday 6/2/45. I was then employed as Driver/Operator in a 'Dingo' armoured car - which was great fun.

In March 1945 the Allies made a massive attack over the Rhine, in which we took part, and successfully entered Germany on a broad front.

The 52nd Division progressed through the Ruhr until we reached and over-ran Bremen. Our Squadron was then quickly re-directed to Stalag XB, which was a prison camp that had been converted into a concentration camp. I won't describe the terrible conditions in that place. Whilst we were there the unconditional surrender of the Germans took place and the war in Europe was at last ended.

We spent the next 11 months or so in doing duty as an occupation army with most of it spent in keeping the peace between rampant ex-POWs and the largely unprotected population.

Then in April 1946 we were merged with the Lothian & Border Horse until July when they were disbanded and we were used to reinforce the 14th/20th Kings Hussars - part of the Regular Army, and now housed in an ex-German barracks in the town of Wuppertal. Now, instead of armoured cars, we were equipped with light tanks which were also great fun.

Then, in June 1947, after another long year of waiting, it became my turn to be demobilised.

After I got home I spent a couple of months in getting acclimatised to civvy street before finding that I had been fortunate in being accepted back into the Blackpool Fire Service.

I spent the next 30 years in the Service, rising through the ranks to finally achieve the position of Divisional Officer.”

Normandy June 1944

“We arrived off the shore of Normandy in the late morning. 'Gold' Beach near the village of Arromanches, which was our first destination, had already been captured by the assault troops of the Hampshire Regiment, and it was now possible for vehicles to be disembarked on to the beach and directed to designated areas for the purpose of de-waterproofing the vehicles and preparing to advance into the bridgehead.

The LST dropped anchor and the remaining Rhino was untied from the side of the ship and made its way round the bows, ready to be attached to the gangway which projected forwards when the bow doors opened. It was then discovered that the coupling gear had been smashed and this sparked off a frenzied burst of activity to try to tie the units together with ropes. However, ropes are flexible by necessity, and the choppy seas made it almost impossible to hold both units in line; but with the aid of a couple of small motor-boats, pushing away like tug boats, they became near enough to go for it and our Troop made the transfer across.

Soon we were running in to the beach and the Rhino bottomed out. The light armoured car (Recce Car) in which I was a crew member was the first to drive off, and in my elevated position in the turret I felt like a submarine commander, especially when we suddenly dropped into a bomb hole which was concealed beneath the water and only the turret was left exposed.”

“The Beach Party had been well trained for this situation and had the de-waterproofing area completely organised and running smoothly. Although I almost threw a spanner in the works!

My armoured car had been fitted with a device, which I had contrived, to allow me to operate the smoke canister gun without having to lean outside the turret. Basically, it was a bike brake mechanism, which was attached at one end to the gun and, at the other end, the brake grip was attached to my seat support. Whilst the driver was removing the waterproofing from the engine, the Officer went to a quick 'O' Group (Officers briefing) and the radio-operators tuned in their radio transmitters to the H.Q. transmitter. This was quite a delicate operation and it was at its finest point when my elbow touched against the trigger. Bang! went the smoke discharger - and as I quickly bobbed my head out I could see the smoke bomb heading straight into the middle of a wired off field, with dozens of painted notices showing the sign of a skull and cross-bones and the words "Achtung Minen". It didn't take a genius to recognise that my bomb was landing in a German mine-field, and the mines were too close for comfort.

I ducked down inside my turret and held my breath........ Nothing - oh good! Then Bang! Bang! Bang! ..... I realised it was someone banging on the turret. When I popped my head back out I was confronted with the angry face of the Beach Officer - a Major - whose features reminded me strongly of the Medical Officer with whom I had been acquainted in Scarborough; complete with black curly moustache, but perhaps even stronger on the language!”

“Soon the various sections of our Regiment were ready to move off to try to reach their pre-arranged target locations. Ours was a wooded hill about 15 miles inland, and our role was to 'seize and hold' it, until the main body of troops could relieve us. It was soon quite obvious that, because of our delayed landing, there was no possibility of us reaching our target that day.

As we drove off the beach, through a pathway made through the minefield and on to a narrow road that ran in a southerly direction, a huge anti-aircraft barrage opened up from the multitude of ships which lay offshore. As the barrage drew nearer I spotted a German plane flying very fast and very low as it fled southwards directly over our heads. I quickly joined the fading barrage and emptied my Bren gun magazine in the direction of the speeding ‘hornet’ as it disappeared out of sight. Despite my effort being in vain I felt great satisfaction in at last being able to throw things back at the Germans.

I remember nothing about our advance during the remainder of the day, only that we eventually had to give way to the coming of the night.”

“My only memories of that first night were that we had to remain standing in the pitch blackness, not daring to make a sound as we had no idea of how close we were to the Germans. We were fortified by a tiny drop of rum, which barely covered the bottom of our tin mugs, and a 'keep awake pill'. Nothing happened all night but we were all relieved when dawn broke and we were able to start off again.”

The Division had landed on Gold Beach, Normandy, on June 6th and fought through Europe up to Arnhem, Holland. Because of the reduction in personnel it was decided that the Division would be disbanded and the remaining personnel be transferred to other units. With this in mind we, 61st Reconnaissance Regiment, were sent back to a small town called Iseghem, which is situated in Belgium, close to the French border. We were billeted in various houses, cafe s and so on, and our H.Q. and cook-house was situated in the railway goods yard. All our vehicles and equipment were taken to a dump somewhere on the road to Antwerp. We had a few days of wonderful bliss. Nothing to do but have a few drinks in the cafe s and idle our time away.

We hadn't reckoned on the Germans. They had realised that the defensive strength of the US Army in the Belgian Ardennes forest was not good, with only 4 Divisions holding a front of 80 miles long. Hitler himself had ordered 3 Armies, totalling twenty-one Divisions (although well below strength), to be assembled in Germany ready for a huge counter-attack. This began on December 16th, meeting with great initial success and the American defence lines were cut to ribbons.

The situation was becoming very serious, as the whole 'sharp-end' of the Allied forces were in danger of being isolated. The British forces directed a push down from the north onto the advancing Germans. We were given 24 hours to reclaim our vehicles and equipment and move out to the Ardennes. This we did.

We arrived at Namur a few days before Christmas, and were immediately given the task of contacting a forward unit of US Engineers who had been instructed to blow a bridge over a small river ( I believe the Ourthe) whenever they sighted the German advance. The orders had now been changed to 'blow up the bridge regardless', but radio contact with the Engineers had been lost.

We set off on our mission and we were shocked to see convoys of US troops retreating in total panic. They threw us some fags and shouted that we were going the wrong way.

We approached our destination, and turned a corner to see that the road ran down into a steep valley, with a similar road running round and down the cliffs on the other side. At that moment we heard a loud explosion and knew that the bridge had been blown. We continued for a short way down the road before spotting the US Engineers running up behind the hedgerow and waited for them to arrive. It was then that I observed a German tank on the road across the valley and, almost immediately, a puff of smoke from his 88 mm. gun. There was a whoosh as the shell screamed over my head and took a lump out of the road and part of the tyre from the armoured car which stood a few yards behind me. Within a few seconds our armoured cars had disappeared up the road and round the corner, in reverse.

“After the huge gamble by the Germans to break through the Ardennes, which came to a disastrous failure, the 61st Reconnaissance Regiment was broken up during January 1945.

I was then posted to C Squadron of the 52nd (Lowland) Scots Recce Regt.. They had trained in Scotland for most of the war and bore a 'MOUNTAIN' flash on their tunics.

Strangely they had only seen warfare in mountainless Holland before I joined them on my birthday 6/2/45. I was then employed as Driver/Operator in a 'Dingo' armoured car - which was great fun.

In March 1945 the Allies made a massive attack over the Rhine, in which we took part, and successfully entered Germany on a broad front.

The 52nd Division progressed through the Ruhr until we reached and over-ran Bremen. Our Squadron was then quickly re-directed to Stalag XB, which was a prison camp that had been converted into a concentration camp. I won't describe the terrible conditions in that place. Whilst we were there the unconditional surrender of the Germans took place and the war in Europe was at last ended.

We spent the next 11 months or so in doing duty as an occupation army with most of it spent in keeping the peace between rampant ex-POWs and the largely unprotected population.

Then in April 1946 we were merged with the Lothian & Border Horse until July when they were disbanded and we were used to reinforce the 14th/20th Kings Hussars - part of the Regular Army, and now housed in an ex-German barracks in the town of Wuppertal. Now, instead of armoured cars, we were equipped with light tanks which were also great fun.

Then, in June 1947, after another long year of waiting, it became my turn to be demobilised.

After I got home I spent a couple of months in getting acclimatised to civvy street before finding that I had been fortunate in being accepted back into the Blackpool Fire Service.

I spent the next 30 years in the Service, rising through the ranks to finally achieve the position of Divisional Officer.”

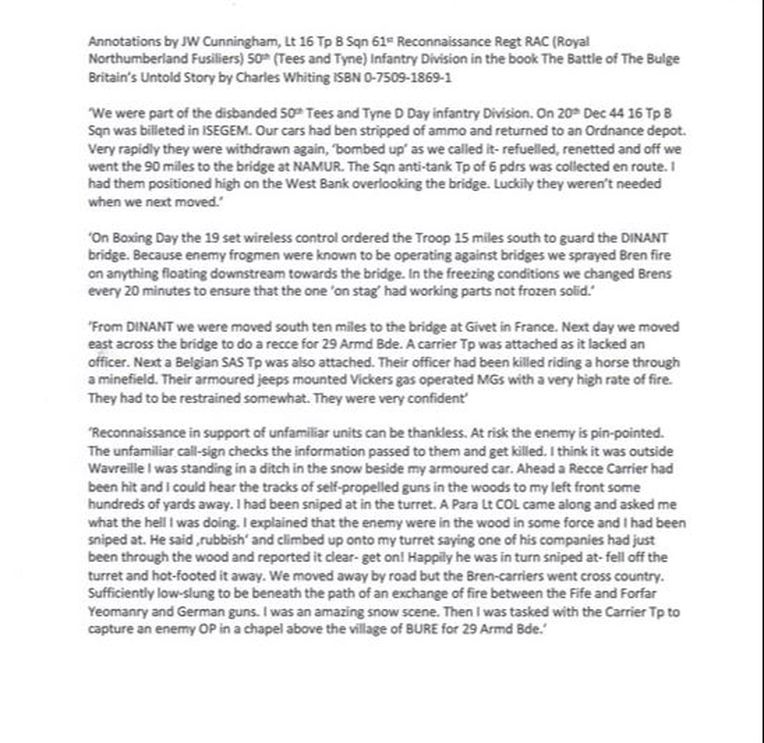

Lt JW (Bill) Cunningham

the above information about JW (Bill) Cunningham was kindly supplied by his son Ian Cunningham

My Last Night with the Regiment

By Thomas Graham

About 6pm we ‘harboured’ and were told we were staying the night. Good, we thought, a nice chance for a wash and shave.

First we had a meal, (got ready by the cook, who was one of the drivers). He prepared it while we were cleaning our weapons. The food of course was tinned, spuds, carrots, etc, the duff was Rice also tinned, which we all liked. We all enjoyed the meal as we could linger over it, which was a very rare occasion.

While we were eating we were talking and planning how to spend the few remaining hours of daylight. Somebody suggested going along to find a village and try and obtain some beer. I wasn’t for that as I was tired and intended ‘kipping’ down early.

We had collected quite a crowd round us by now, old men young couples, children, Belgians, dozens of them. This audience used to watch us whether we were eating, working, idling in fact everything we did in ‘harbour’ we had them watching us. At first we used to be quite embarrassed, day in, day out a group of people watching every movement we made, but gradually we got used to it and looked on it as an every-day occurrence. If there only happened to be a few children we used to give the youngest a helping of what we were having, and try to give the older ones some too, if it would go round, we used to pity them, and they used to rather expect it.

They had a bitter experience during the occupation.

After the meal, we washed our mess tins knife and fork etc, in a tin of water which had been on the fire while we had been eating. After emptying this tin we put on fresh water to boil for washing and shaving, six men to every tin. I was fourth I line to use our tin, after washing, shaving and doing my hair I just stayed in my shirt sleeves ( I hadn’t worn my jacket all day).

After rerolling my sleeves and replacing my kit I wandered across to the fire, already quite a few of the lads were there and Jock was giving them a tune on the mouth-organ, and some of the others were either whistling of humming the refrains. I had no voice for singing so I joined in with a bit of humming. Jock then started playing ‘Jealousy’, it was my favourite tune and it made me feel homesick. I first heard in the ‘Futurist’ Cinema at Scarborough. I went to a matinee with a girl named Joan, she lived in York and was in Scarborough on a holiday, and this tune was played, it always stuck in my mind. Joan was on a six week stay there and I met her at the end of the first week there, we had a lot of decent fun together.

Someone nudged me and asked for a light, and it brought me back to that Belgian orchard. The sing-song continued with ‘Tipperary’ and ‘Pack up your troubles’, this some of our audience joined in trying to re-collect the words, I cannot really explain the feeling, but it made us feel good inside to hear them, (they knew that they were now amongst friends and could sing the songs they wanted and not fear any consequences), they were now able to speak as much English as they able to.

We all loved a sing-song and it went on till nearly dark. With rather rusty throats we drifted away in ones and twos, I left also and made my way to my ‘kip’ I got in the carrier beside the wireless set. I put my pack behind me to act as a pillow, my great-coat was my blanket, I put my knees right up to the wireless set and snuggled right down into my ‘bed space’, it takes a few days to get used to but it felt good to relax, I put my gas-cape over my head and shoulders and my ground-sheet over my legs as protection against the rain and pulled my rifle closer to me, sticking the muzzle out,(it always pays to be prepared).

It did start to rain slightly put I went to sleep and took no notice of it.

I was rudely awaked by someone pulling down my gas-cape and shouting, “come on, out of it, were moving”. The caller was the Troop Sergeant, “moving”, I thought we had just gone to sleep, besides, it was still dark and we had been promised the day off tomorrow to rest. These and other thoughts were flying through my brain. I looked at my wrist watch, 1-40am. The Troop Sgt, came back saying, ”Come on lads, get packed up, we’re moving”.

Graham, he addressed me personally, “you travel in Cpl Caddle carrier, Chanley will take over your set”. (Chanley was the other operator, and we often used to switch over, especially during long runs to prevent boredom, because its agony sitting in front of a set ear-phones buzzing, the vehicle bouncing all over the road).

I collected what I would require and boarded Cpl Caddle’s carrier. The remaining few minutes I spent getting the inter-troop wireless set straightened up and settling in. Our Troop moved out at 2-10am, following 15 Troop, we had been told we were going to Antwerp. An Armoured Brigade was an hour in front of us, they were to knock out any heavy stuff that was in our path, and when we caught up with them we had to go through them and get to |Antwerp as soon as possible. After passing the armoured stuff we had to by-pass any resistance rather than lose time over them.

We had done many a job like this before but this was slightly different, there was a canal to overcome, a thing we hadn’t done before. This canal was the ALBERT CANAL.

According to the Sqdn Commander (before moving off), there was only one bridge left over this canal, and our first job was to get this bridge intact before the Germans had a chance to blow it up, but we should reach the canal about the same time as the armoured column and they should be a big help in support.

On the main road we got moving very fast, considering it was dark and no lights on the vehicles were allowed. It was frosty and the cold wind bit our faces and caused our eyes to water. I put on my overcoat and buttoned the collar as high as I could, I also removed my steel ‘topie’ and put on my beret, (this stayed on better in the wind). My body was nice and warm, (Robbo, the gunner and I had the engine between us and this kept us warm. The driver Matthews and Cpl Caddle, the crew commander, both in the front, completed our vehicle crew). We used to interchange on long runs to try to keep everyone comfortable, I used to change with Matthews, as I could drive and Robbo changed with Bill (Cpl Caddle), Robbo couldn’t drive.

After we got started Bill told Robbo and I to try and catch up on a bit of sleep.

When I woke up the convoy was halted in the side of the road, Bill said the Troop Commanders were at a meeting and it was thought we were going to split up and make for Antwerp individually in a rough fan shape. While we were waiting Bill asked me to switch places with him, he was frozen he said. Matthews was still driving and said he could manage a bit further.

Major Alexander came up the road just then in his L.R.C. ordering us to start up and prepare to move out. As we moved onto the road I looked at the time, 6-20am. I thought we should be nearing the canal by now, but we travelled almost an hour and a half before we saw or heard anything. We were halted again, and into a side road.

In the distance fires could be seen, and the thud of heavy guns could be heard. Another ‘O’ group was called, (Troop Commanders report to Sqdn Commander). While this was going on Bill was standing on the top of the carrier and viewing the fighting area through binoculars. He said he thought there was a lot of machine gun fire and he thought he had been able to distinguish a few tanks over there.

The Troop Commander returned and called for Crew Commanders. Bill came back in about five minutes and started explaining to us what was to take place.

“That fire over there is where the bridge is situated, our people have got it intact but Jerry still had a few machine-guns directed against it. Carriers and armoured cars to go across, 3 tonners and 15cwts to stay this side”, Start up and follow Jock finished Bill.

I was still in the front with Matthews when we moved out into the road after Jock. We covered about two or three miles at very fast speed. Rounding a rather sharp bend we got our first real view of the canal and more to our front was the bridge we were to cross. Houses were on fire on both banks of the canal, (although there was only two houses on our side of the water).

We slowed down to a crawl, they were trying to sort the vehicles out and doing their best in the narrow road most of the drivers cursing Alec (the Major) for not doing this earlier).

We kept edging up slowly, 15 Troop are now on the bridge. Our front vehicles reach bridge as Alec comes nearer, “keep your head Jerry has still got machine guns covering the bridge”.

Our carrier starts to cross the bridge and Alec’s warning is recalled as we hear the rattle of bullets on the side of the carrier. A stray bullet whizzes between Matthews and I, strikes the radiator cap and ricochet’s away like an angry bee, making us crouch still further down onto the sand-bags ( on the floor of the carrier as protection against mines).

We reach the far side of the bridge and pull over in the cover of a house, the road seems to be blocked further ahead and the vehicles in front of us seem to be all seeking some kind of shelter. As we look round we see there is a tank on the road ahead trying to engage the machine gun post, and just round the corner of the house we can just see the German machine gun post, it is well dug in and the tank fire, and all the rest of the fire directed against it is not having the slightest bit of effect on it.

In front of us the vehicles start moving and when the one in front has gone a few yards we move out after him. It seems as though the enemy has forgotten us as there is no firing in our direction. We keep moving at a slow pace, our armoured cars have their Besa’s and two pounders firing at the machine gun nests. Looking through the visors we see this, and also see the bullets hitting the side of the carrier in front and see the ones that are missing as the Germans are using a lot of tracers.

There is a little village about two miles straight up this road and the Germans gun positions are dug in a railway embankment which carries the railway into the same village.

I look over Matthews head towards the enemy position and see our infantry have arrived and are at the foot of the embankment, starting the ascent. One of our tanks fires at them, mistaking them for Germans. A member of the ‘Foot Sloggers’ calmly stands up, turns round and signals the tank to cease firing at that area. (I often marvel at the way these fellow turn up when they are required they just seem to appear out of thin air).

The German machine-gun post is still pouring out all the fire-power it can. This post must be manned by SS men, because the beating it’s taking, the ordinary German soldier would have capitulated by this time. The tanks have 6 pounders and machine guns, armoured cars have 2 pounders and Besa’s and the carriers have Bren guns on it, and still it is as safe looking as it was at the beginning. As I look up towards it the enemy post directs it fire on us, and the bullets thud on the carrier sides as we still crawl along the road. I squeeze down and decide I will use the visor for observation. Matthews seems to think the same, I can see him out of the corner of my eye lean down and bring his face close to his own visor.

The carriers in front are still progressing, and there is one or two houses on the left of the road further along. The machine gun fire seems to be increasing against us.

Just as we are almost level with the houses, Matthews grits his teeth and spurts the vehicle forward and catches right up to the carrier in front. Suddenly his head falls forward on to the steering wheel, I turn round towards him and nudge him, he just lurches side-ways and as he slips down I see he has a round hole in his fore-head, and it is dripping red.

The Carrier is lurching along the road and swinging to the right of the road, I lean across and grasp the steering-wheel and try to keep it straight, at the same time I see a trail of tracer bullets being sprayed at this carrier. Just then, as I pull the carrier to the left, my left arm drops to my side. I pull the steering-wheel over with my right arm and the carrier bumps off the road to the left, I try to reach the brake but without success. The carrier continues and I see we are heading right towards one of the houses, I try to get the brake on again, still no effect. The next thing I know there is bricks falling into the carrier and the engine stalls.

I have another look at Matthews, yes he is dead. I put arms forward and intend to grab the edge of the carrier but my left arm doesn’t come up it stays limp, a broken arm.

As I reach down to grasp my left sleeve to tuck it into my great-coat, I notice a lot of blood and some bits of flesh on my chest. All this can’t have come from my arm. The great-coat was also slashed as though had been trying out a butchers knife. Millions of thoughts flashed through my brain. My face is rather as though it has been out in a keen wind, I remember I had first felt this when my arm had been hit.

I must have been hit somewhere in the FACE!!!

My goodness !!! My mind was racing twenty to the dozen. I began to pray. To pray hard.

I decided to get out of the carrier, so standing up I began to dismount. I struggled on to the carrier and stood there for about thirty seconds getting my bearings. The carrier in colliding with the house had made quite a hole, so I scrambled down and through this as best I could and got inside the house.

Bill and Robbo were already in, and seeing me they came towards me and helped me away from the hole, Bill told me to lie down. Ignoring this advice I went towards a chair, sitting down I had a look round and saw we were in a typical peasant’s cottage, rough furniture etc, including an old-fashioned pump to my right.

An old man had appeared in the room, from the cellar I think. He just stood there, staring at me, I didn’t blame him, I guess I looked a terrible site.

Seeing the pump I felt very thirsty and staggered over and made signs I wanted a drink. Bill and Robbo came over and guided me into another room and made me lie down. Bill was saying that Matthews was dead, he had just had a look. Carrying on the conversation with Robbo, thinking I wasn’t in a fit state to understand Bill referred to me saying, “he will be dead shortly. It’s just nerves keeping him alive!!!!”.

I prayed again. Thought of home. Will I ever see England again? What happens now? What should I do? Am I dying? Will I die?

Millions of thoughts rushed through my mind. Visions of home flashed before me. My past life. Was I really dying? I had read that men lived their lives over again while they were dying.

But I didn’t want to die. I won’t die I would live just to show them they were wrong.

Getting up I began staggering around and my senses seemed to clear and I heard the hail of death was still outside. How long I stayed in that house I don’t know. Some people will say that time drags in a situation like this, others maintain it flies past, but I had no idea of the passage of time.

I can still recall that room and that house, there was a lot of straw on the floor, and it seemed that everything of any value had been either taken to a safer place or looted by the Germans.

After I got up from the straw Jock came in to say there was a stretcher on the way, (I still don’t know who sent it).

Bill, Robbo, jock and the fellow who brought the stretcher all had different ideas on how I should lie on the stretcher. All of them advising me yet scared to touch me for fear of hurting me. I finally managed to get myself on the stretcher and Jock took the head end and the stretcher fellow took the foot.

Just as we reached the door-way a burst of machine gun fire plastered the door. They laid me down for a few minutes until it sounded safer outside. Before lifting the stretcher again the stretcher-bearer picked up his big 3ft x 2ft Red Cross flag and displayed it as we moved out of the house. I was carried along behind a hedge-row, I tried to close my eyes to shut out the bumping and jolting, I tried to relax.

Then it happened, ne moment I was being carried on the stretcher, the next moment I was hitting the ground with a bump. It all happened so suddenly, I didn’t quite know what it was all about. (I learned later that the stretcher-bearer had been hit). I dimly recall Jock telling me to lie still. I don’t know if I lay still or not, and how long we lay there I have no idea. It may have been thirty seconds or it could have been thirty minutes.

The next thing I remember is walking along the road towards the bridge. I remember saying to myself that speed was the essential thing and I hurried as best I could. Scared? No I don’t think so, although I was walking along in the open. All I wanted to do was to get away from there. Some-one helped me along the last hundred yards or so down towards the bridge and just before we reached it he steered me to the right, off the road towards one of the houses. There was a 15cwt truck, as we got nearer I saw it was our own First Aid Vehicle. It was drawn across the front door as a barricade.

The Corporal Medical orderly just stood and gaped at me, after the shock he started to dress my wounds by taking my Field Dressing out of my trouser pocket and bandaging my face. He called for a second dressing and also applied this to my face. He the guided me round the corner of the door and sat me on a box just in the doorway. I was waiting for him to start on my arm, but he started to go away so I got up and followed him and made signs that I wanted paper and pencil. He gave me the paper and some-one else handed me a pencil. The orderly held the paper against the door of the truck while I wrote, “my arm is broken as well”, reading the paper the orderly looked at me with a frown on his face, I pointed to my left arm. He nodded and started cutting away the left sleeve of my great-coat. He applied a dressing to it and put my arm in a sling. Again he helped me to the box and sat me down.

There was a few more fellows in the room with bandages or dressings on their arms or legs, they all seemed to be drinking tea. That made me seem very thirsty and I would have been thankful just to be able to have a mouthful of it. The Sergeant Major was also there, he seemed to be sorting out some boxes, and giving orders to different men in the house.

I seemed to sit on that box for hours, I wasn’t unconscious but I was in a bit of a daze. There seemed to be plenty of activity going on around me, especially to my left and outside. I could hear vehicles changing gear as they climbed the incline outside.

I was taken outside and placed in a Jeep, which started off towards the bridge. As we were on the bridge a shell landed just to our right and made a hole in the bridge. I was taken to another First Aid post, this time staffed by RAMC there was also a Padre of a Religion I never found out. The RAMC orderlies decided to leave the face dressing as they were but they added a splint to my arm.

It was then a series of First Aid Posts and Field Dressing Stations all the way until I was passed back to Brussels. From the Hospital there I was taken by Army Ambulance to the aerodrome near Brussels and put aboard a Red Cross Ambulance plane. I was half lying, half sitting on the stretcher and was placed near a window, I remember wishing that they would come and open the window as I was sweating.

A medical orderly came across to see if I was all right, and then we were off.

The journey across to England seemed short, I may have dozed now and again, but I remember the plane trip, I remember looking out of the window and seeing the coast of England as we crossed it.

The next thing I remember is being in a kind of Hospital ward, it was really the aerodrome reception room. There is a lot of beds, and all the patients are having a meal. The chap in the next bed I see is having what seems to be steak and chips. A forces Chaplain comes over to my bed side and talks to me, he also asks me to sign one of them official cards to send home to say that I have been wounded and been admitted to Hospital. I move on again to other reception centres and Hospitals until I finally arrive at Basingstoke, and am admitted to the plastic surgery there, where I spend the next six years of my life being patched up and made presentable to the world outside.

Kindly supplied by his son Tony.

By Thomas Graham

About 6pm we ‘harboured’ and were told we were staying the night. Good, we thought, a nice chance for a wash and shave.

First we had a meal, (got ready by the cook, who was one of the drivers). He prepared it while we were cleaning our weapons. The food of course was tinned, spuds, carrots, etc, the duff was Rice also tinned, which we all liked. We all enjoyed the meal as we could linger over it, which was a very rare occasion.

While we were eating we were talking and planning how to spend the few remaining hours of daylight. Somebody suggested going along to find a village and try and obtain some beer. I wasn’t for that as I was tired and intended ‘kipping’ down early.

We had collected quite a crowd round us by now, old men young couples, children, Belgians, dozens of them. This audience used to watch us whether we were eating, working, idling in fact everything we did in ‘harbour’ we had them watching us. At first we used to be quite embarrassed, day in, day out a group of people watching every movement we made, but gradually we got used to it and looked on it as an every-day occurrence. If there only happened to be a few children we used to give the youngest a helping of what we were having, and try to give the older ones some too, if it would go round, we used to pity them, and they used to rather expect it.

They had a bitter experience during the occupation.

After the meal, we washed our mess tins knife and fork etc, in a tin of water which had been on the fire while we had been eating. After emptying this tin we put on fresh water to boil for washing and shaving, six men to every tin. I was fourth I line to use our tin, after washing, shaving and doing my hair I just stayed in my shirt sleeves ( I hadn’t worn my jacket all day).

After rerolling my sleeves and replacing my kit I wandered across to the fire, already quite a few of the lads were there and Jock was giving them a tune on the mouth-organ, and some of the others were either whistling of humming the refrains. I had no voice for singing so I joined in with a bit of humming. Jock then started playing ‘Jealousy’, it was my favourite tune and it made me feel homesick. I first heard in the ‘Futurist’ Cinema at Scarborough. I went to a matinee with a girl named Joan, she lived in York and was in Scarborough on a holiday, and this tune was played, it always stuck in my mind. Joan was on a six week stay there and I met her at the end of the first week there, we had a lot of decent fun together.

Someone nudged me and asked for a light, and it brought me back to that Belgian orchard. The sing-song continued with ‘Tipperary’ and ‘Pack up your troubles’, this some of our audience joined in trying to re-collect the words, I cannot really explain the feeling, but it made us feel good inside to hear them, (they knew that they were now amongst friends and could sing the songs they wanted and not fear any consequences), they were now able to speak as much English as they able to.

We all loved a sing-song and it went on till nearly dark. With rather rusty throats we drifted away in ones and twos, I left also and made my way to my ‘kip’ I got in the carrier beside the wireless set. I put my pack behind me to act as a pillow, my great-coat was my blanket, I put my knees right up to the wireless set and snuggled right down into my ‘bed space’, it takes a few days to get used to but it felt good to relax, I put my gas-cape over my head and shoulders and my ground-sheet over my legs as protection against the rain and pulled my rifle closer to me, sticking the muzzle out,(it always pays to be prepared).

It did start to rain slightly put I went to sleep and took no notice of it.

I was rudely awaked by someone pulling down my gas-cape and shouting, “come on, out of it, were moving”. The caller was the Troop Sergeant, “moving”, I thought we had just gone to sleep, besides, it was still dark and we had been promised the day off tomorrow to rest. These and other thoughts were flying through my brain. I looked at my wrist watch, 1-40am. The Troop Sgt, came back saying, ”Come on lads, get packed up, we’re moving”.

Graham, he addressed me personally, “you travel in Cpl Caddle carrier, Chanley will take over your set”. (Chanley was the other operator, and we often used to switch over, especially during long runs to prevent boredom, because its agony sitting in front of a set ear-phones buzzing, the vehicle bouncing all over the road).

I collected what I would require and boarded Cpl Caddle’s carrier. The remaining few minutes I spent getting the inter-troop wireless set straightened up and settling in. Our Troop moved out at 2-10am, following 15 Troop, we had been told we were going to Antwerp. An Armoured Brigade was an hour in front of us, they were to knock out any heavy stuff that was in our path, and when we caught up with them we had to go through them and get to |Antwerp as soon as possible. After passing the armoured stuff we had to by-pass any resistance rather than lose time over them.

We had done many a job like this before but this was slightly different, there was a canal to overcome, a thing we hadn’t done before. This canal was the ALBERT CANAL.

According to the Sqdn Commander (before moving off), there was only one bridge left over this canal, and our first job was to get this bridge intact before the Germans had a chance to blow it up, but we should reach the canal about the same time as the armoured column and they should be a big help in support.

On the main road we got moving very fast, considering it was dark and no lights on the vehicles were allowed. It was frosty and the cold wind bit our faces and caused our eyes to water. I put on my overcoat and buttoned the collar as high as I could, I also removed my steel ‘topie’ and put on my beret, (this stayed on better in the wind). My body was nice and warm, (Robbo, the gunner and I had the engine between us and this kept us warm. The driver Matthews and Cpl Caddle, the crew commander, both in the front, completed our vehicle crew). We used to interchange on long runs to try to keep everyone comfortable, I used to change with Matthews, as I could drive and Robbo changed with Bill (Cpl Caddle), Robbo couldn’t drive.

After we got started Bill told Robbo and I to try and catch up on a bit of sleep.

When I woke up the convoy was halted in the side of the road, Bill said the Troop Commanders were at a meeting and it was thought we were going to split up and make for Antwerp individually in a rough fan shape. While we were waiting Bill asked me to switch places with him, he was frozen he said. Matthews was still driving and said he could manage a bit further.

Major Alexander came up the road just then in his L.R.C. ordering us to start up and prepare to move out. As we moved onto the road I looked at the time, 6-20am. I thought we should be nearing the canal by now, but we travelled almost an hour and a half before we saw or heard anything. We were halted again, and into a side road.

In the distance fires could be seen, and the thud of heavy guns could be heard. Another ‘O’ group was called, (Troop Commanders report to Sqdn Commander). While this was going on Bill was standing on the top of the carrier and viewing the fighting area through binoculars. He said he thought there was a lot of machine gun fire and he thought he had been able to distinguish a few tanks over there.

The Troop Commander returned and called for Crew Commanders. Bill came back in about five minutes and started explaining to us what was to take place.

“That fire over there is where the bridge is situated, our people have got it intact but Jerry still had a few machine-guns directed against it. Carriers and armoured cars to go across, 3 tonners and 15cwts to stay this side”, Start up and follow Jock finished Bill.

I was still in the front with Matthews when we moved out into the road after Jock. We covered about two or three miles at very fast speed. Rounding a rather sharp bend we got our first real view of the canal and more to our front was the bridge we were to cross. Houses were on fire on both banks of the canal, (although there was only two houses on our side of the water).

We slowed down to a crawl, they were trying to sort the vehicles out and doing their best in the narrow road most of the drivers cursing Alec (the Major) for not doing this earlier).

We kept edging up slowly, 15 Troop are now on the bridge. Our front vehicles reach bridge as Alec comes nearer, “keep your head Jerry has still got machine guns covering the bridge”.

Our carrier starts to cross the bridge and Alec’s warning is recalled as we hear the rattle of bullets on the side of the carrier. A stray bullet whizzes between Matthews and I, strikes the radiator cap and ricochet’s away like an angry bee, making us crouch still further down onto the sand-bags ( on the floor of the carrier as protection against mines).

We reach the far side of the bridge and pull over in the cover of a house, the road seems to be blocked further ahead and the vehicles in front of us seem to be all seeking some kind of shelter. As we look round we see there is a tank on the road ahead trying to engage the machine gun post, and just round the corner of the house we can just see the German machine gun post, it is well dug in and the tank fire, and all the rest of the fire directed against it is not having the slightest bit of effect on it.

In front of us the vehicles start moving and when the one in front has gone a few yards we move out after him. It seems as though the enemy has forgotten us as there is no firing in our direction. We keep moving at a slow pace, our armoured cars have their Besa’s and two pounders firing at the machine gun nests. Looking through the visors we see this, and also see the bullets hitting the side of the carrier in front and see the ones that are missing as the Germans are using a lot of tracers.

There is a little village about two miles straight up this road and the Germans gun positions are dug in a railway embankment which carries the railway into the same village.

I look over Matthews head towards the enemy position and see our infantry have arrived and are at the foot of the embankment, starting the ascent. One of our tanks fires at them, mistaking them for Germans. A member of the ‘Foot Sloggers’ calmly stands up, turns round and signals the tank to cease firing at that area. (I often marvel at the way these fellow turn up when they are required they just seem to appear out of thin air).

The German machine-gun post is still pouring out all the fire-power it can. This post must be manned by SS men, because the beating it’s taking, the ordinary German soldier would have capitulated by this time. The tanks have 6 pounders and machine guns, armoured cars have 2 pounders and Besa’s and the carriers have Bren guns on it, and still it is as safe looking as it was at the beginning. As I look up towards it the enemy post directs it fire on us, and the bullets thud on the carrier sides as we still crawl along the road. I squeeze down and decide I will use the visor for observation. Matthews seems to think the same, I can see him out of the corner of my eye lean down and bring his face close to his own visor.

The carriers in front are still progressing, and there is one or two houses on the left of the road further along. The machine gun fire seems to be increasing against us.

Just as we are almost level with the houses, Matthews grits his teeth and spurts the vehicle forward and catches right up to the carrier in front. Suddenly his head falls forward on to the steering wheel, I turn round towards him and nudge him, he just lurches side-ways and as he slips down I see he has a round hole in his fore-head, and it is dripping red.

The Carrier is lurching along the road and swinging to the right of the road, I lean across and grasp the steering-wheel and try to keep it straight, at the same time I see a trail of tracer bullets being sprayed at this carrier. Just then, as I pull the carrier to the left, my left arm drops to my side. I pull the steering-wheel over with my right arm and the carrier bumps off the road to the left, I try to reach the brake but without success. The carrier continues and I see we are heading right towards one of the houses, I try to get the brake on again, still no effect. The next thing I know there is bricks falling into the carrier and the engine stalls.

I have another look at Matthews, yes he is dead. I put arms forward and intend to grab the edge of the carrier but my left arm doesn’t come up it stays limp, a broken arm.

As I reach down to grasp my left sleeve to tuck it into my great-coat, I notice a lot of blood and some bits of flesh on my chest. All this can’t have come from my arm. The great-coat was also slashed as though had been trying out a butchers knife. Millions of thoughts flashed through my brain. My face is rather as though it has been out in a keen wind, I remember I had first felt this when my arm had been hit.

I must have been hit somewhere in the FACE!!!

My goodness !!! My mind was racing twenty to the dozen. I began to pray. To pray hard.

I decided to get out of the carrier, so standing up I began to dismount. I struggled on to the carrier and stood there for about thirty seconds getting my bearings. The carrier in colliding with the house had made quite a hole, so I scrambled down and through this as best I could and got inside the house.

Bill and Robbo were already in, and seeing me they came towards me and helped me away from the hole, Bill told me to lie down. Ignoring this advice I went towards a chair, sitting down I had a look round and saw we were in a typical peasant’s cottage, rough furniture etc, including an old-fashioned pump to my right.

An old man had appeared in the room, from the cellar I think. He just stood there, staring at me, I didn’t blame him, I guess I looked a terrible site.

Seeing the pump I felt very thirsty and staggered over and made signs I wanted a drink. Bill and Robbo came over and guided me into another room and made me lie down. Bill was saying that Matthews was dead, he had just had a look. Carrying on the conversation with Robbo, thinking I wasn’t in a fit state to understand Bill referred to me saying, “he will be dead shortly. It’s just nerves keeping him alive!!!!”.

I prayed again. Thought of home. Will I ever see England again? What happens now? What should I do? Am I dying? Will I die?

Millions of thoughts rushed through my mind. Visions of home flashed before me. My past life. Was I really dying? I had read that men lived their lives over again while they were dying.

But I didn’t want to die. I won’t die I would live just to show them they were wrong.

Getting up I began staggering around and my senses seemed to clear and I heard the hail of death was still outside. How long I stayed in that house I don’t know. Some people will say that time drags in a situation like this, others maintain it flies past, but I had no idea of the passage of time.

I can still recall that room and that house, there was a lot of straw on the floor, and it seemed that everything of any value had been either taken to a safer place or looted by the Germans.

After I got up from the straw Jock came in to say there was a stretcher on the way, (I still don’t know who sent it).

Bill, Robbo, jock and the fellow who brought the stretcher all had different ideas on how I should lie on the stretcher. All of them advising me yet scared to touch me for fear of hurting me. I finally managed to get myself on the stretcher and Jock took the head end and the stretcher fellow took the foot.

Just as we reached the door-way a burst of machine gun fire plastered the door. They laid me down for a few minutes until it sounded safer outside. Before lifting the stretcher again the stretcher-bearer picked up his big 3ft x 2ft Red Cross flag and displayed it as we moved out of the house. I was carried along behind a hedge-row, I tried to close my eyes to shut out the bumping and jolting, I tried to relax.

Then it happened, ne moment I was being carried on the stretcher, the next moment I was hitting the ground with a bump. It all happened so suddenly, I didn’t quite know what it was all about. (I learned later that the stretcher-bearer had been hit). I dimly recall Jock telling me to lie still. I don’t know if I lay still or not, and how long we lay there I have no idea. It may have been thirty seconds or it could have been thirty minutes.

The next thing I remember is walking along the road towards the bridge. I remember saying to myself that speed was the essential thing and I hurried as best I could. Scared? No I don’t think so, although I was walking along in the open. All I wanted to do was to get away from there. Some-one helped me along the last hundred yards or so down towards the bridge and just before we reached it he steered me to the right, off the road towards one of the houses. There was a 15cwt truck, as we got nearer I saw it was our own First Aid Vehicle. It was drawn across the front door as a barricade.

The Corporal Medical orderly just stood and gaped at me, after the shock he started to dress my wounds by taking my Field Dressing out of my trouser pocket and bandaging my face. He called for a second dressing and also applied this to my face. He the guided me round the corner of the door and sat me on a box just in the doorway. I was waiting for him to start on my arm, but he started to go away so I got up and followed him and made signs that I wanted paper and pencil. He gave me the paper and some-one else handed me a pencil. The orderly held the paper against the door of the truck while I wrote, “my arm is broken as well”, reading the paper the orderly looked at me with a frown on his face, I pointed to my left arm. He nodded and started cutting away the left sleeve of my great-coat. He applied a dressing to it and put my arm in a sling. Again he helped me to the box and sat me down.

There was a few more fellows in the room with bandages or dressings on their arms or legs, they all seemed to be drinking tea. That made me seem very thirsty and I would have been thankful just to be able to have a mouthful of it. The Sergeant Major was also there, he seemed to be sorting out some boxes, and giving orders to different men in the house.

I seemed to sit on that box for hours, I wasn’t unconscious but I was in a bit of a daze. There seemed to be plenty of activity going on around me, especially to my left and outside. I could hear vehicles changing gear as they climbed the incline outside.

I was taken outside and placed in a Jeep, which started off towards the bridge. As we were on the bridge a shell landed just to our right and made a hole in the bridge. I was taken to another First Aid post, this time staffed by RAMC there was also a Padre of a Religion I never found out. The RAMC orderlies decided to leave the face dressing as they were but they added a splint to my arm.

It was then a series of First Aid Posts and Field Dressing Stations all the way until I was passed back to Brussels. From the Hospital there I was taken by Army Ambulance to the aerodrome near Brussels and put aboard a Red Cross Ambulance plane. I was half lying, half sitting on the stretcher and was placed near a window, I remember wishing that they would come and open the window as I was sweating.

A medical orderly came across to see if I was all right, and then we were off.

The journey across to England seemed short, I may have dozed now and again, but I remember the plane trip, I remember looking out of the window and seeing the coast of England as we crossed it.

The next thing I remember is being in a kind of Hospital ward, it was really the aerodrome reception room. There is a lot of beds, and all the patients are having a meal. The chap in the next bed I see is having what seems to be steak and chips. A forces Chaplain comes over to my bed side and talks to me, he also asks me to sign one of them official cards to send home to say that I have been wounded and been admitted to Hospital. I move on again to other reception centres and Hospitals until I finally arrive at Basingstoke, and am admitted to the plastic surgery there, where I spend the next six years of my life being patched up and made presentable to the world outside.

Kindly supplied by his son Tony.

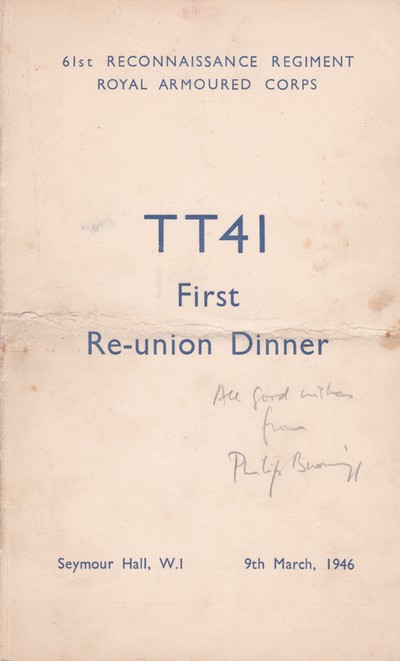

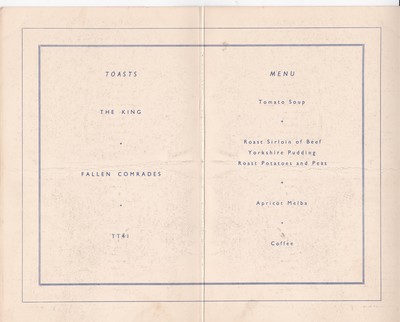

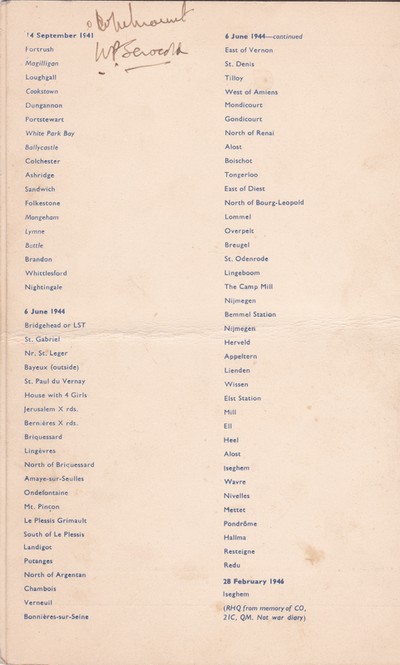

Re-union dinner menu supplied by Mike Lightwing who's father attended this dinner. As you can see it is signed on the front by Lt Col P H A Brownrigg DSO and on the back by Lt Col Sir William Mount.

THE NORTHERN ECHO 22nd July 2010.

The home fires burn still in Reeth, a wartime headquarters for soldiers whose motto was ‘Only the enemy in front’.

REETH’S tranquil in the seductive summer sunshine, a chimney or two gently smoking skywards, the dray wagon assuaging the Buck Inn’s thirst all that disturbs the early afternoon peace. It hasn’t always been so quiet in that glorious Swaledale village. During the Second World War it was home, first, to evacuees from Gateshead and Sunderland, later to hundreds of soldiers from the RASC, RAMC, Royal Engineers and, most memorably of all, the men they called the Reccies.

They were the Reconnaissance Corps – motto “Only the enemy in front” – formed into the Reeth Battle School and commanded for much of the time by Major John Parry, who brought his beagle pack with him.

Now those extraordinary days are to be remembered by the commissioning of a plaque outside what is now the upmarket Burgoyne Hotel but then was the commandeered Hill House, Battle School headquarters. For all concerned it was quite an education. “I’ve got to 72 and still they’re not recognised in any way up here,” says parish councillor James Kendall.

“Most people in Reeth probably know more about the Hartlepool monkey than they do about what happened here during the war.”

The council, keen to back him, hopes to unveil the plaque on Armistice Day. “They were the Commandos of their day, all of them gave something, some gave everything,” says James. “It’s right that Reeth should acknowledge them before all our generation is gone.

“People today tell their kids to be careful on the roads but back then we were growing up with Chieftain tanks and Bren gun carriers all over this little village. “We knew there was a war because all our young men had left, but we didn’t know that a village full of Reccies wasn’t normal until they’d gone. “If it hadn’t been for those boys, we might have had an army in jackboots and grey uniforms instead.”

KEITH JACKSON, a retired Methodist minister, was around 12 when the Reccies arrived, also recalls how – after the Dunkirk evacuation – the RASC had to march the 25 miles from Darlington railway station to Reeth and collapsed, exhausted, on the sunlit green.

“We weren’t scared of the soldiers, rather we emulated them. We’d make uniforms out of brown paper, rifles out of wood. If we needed barbed wire, we’d pull up a few thorn bushes and crawl through those.”

Some still recall the route marches up to Arkengarthdale Moor, the Reccies lined up four or five abreast for 100 yards along the top road, Major Parry as ever cracking the whip. They talk of the assault course by the side of Arkle Beck – the Reccies named locations like Burma Road, Smoky Joe’s Cabin and Bridge of Sighs – the exercises with live ammunition and Very lights, the nightly mock battles that illuminated the sky like fireworks.

Keith remembers that they’d pile out of Sunday School, still in sabbath suits, and head for the handover- hand assault course across the Swale. The result, and the occasional immersion, was inevitable.

Major Parry once ended up in hospital, it’s recalled, after a similar fall from grace. “They’d do all sorts, often overturning their dinghies into the Swale, the fastest flowing river in England,” says Keith. “I don’t know how they survived. They reckoned that Major Parry was a bit mad. Probably it helped to be.”

Barbara Buckingham recalls that her family adopted the Reccies’ cat, called Minniehaha, when the Battle School finally closed. Family cats have carried the name ever since. “They just never seemed to be still,” says Keith Jackson, “always jumping about, always doing things at the double. They really were the front line. They had to learn how to bash through anything.”

The officers were billeted at Cambridge House, up on the Arkengarthdale Road – “a bit exotic,” says James Kendall – the NCOs at Hill House. The local kids did pretty well out of it. “We’d always be stopping by the sergeants’ mess, getting a bottle of pop or a lump of slab cake,” says James. “No one in Reeth went hungry when the Reccies were there, but I wonder the poor troops got any food at all.”

They’d have film shows under canvas at Woodyard Farm, concerts in the Conservative Club which had become Home Guard headquarters and is now the Memorial Hall.Keith’s father was in the Home Guard – “I still remember his rifle in the corner of the house”. He himself became a corporal in the school cadet unit. “It wasn’t that I was military, just in the spirit of the thing.